The Children's Village

An American woman and her Tanzanian business partner have become the legal guardians of nearly 100 children in a village they refuse to call an orphanage because it's home

The following script is from "The Children's Village" which aired on May 1, 2016. Bill Whitaker is the correspondent. Magalie Laguerre-Wilkinson, producer.

Tanzania is an East African country of staggering beauty and devastating poverty. Half the population of 51 million is under the age of 14 --- many of them orphaned, abandoned or abused. For the last 10 years, in a remote northern corner of the country, hundreds of children in need of care have found refuge and protection in a mountainside oasis called the Rift Valley Children's Village. It's not just a safe haven, it's their home. It's run by an American woman, India Howell, and Peter Leon Mmassy, her Tanzanian business partner. They're like "The Odd Couple;" she's impatient and blunt, he's cool and diplomatic. Together they are parents to 94 children and counting -- the biggest extended family we have ever seen. When we heard of this extraordinary place, we had to go see for ourselves.

Driving to Rift Valley Children's Village, Tanzania

CBS NEWS

Tanzania attracts about a million tourists a year and this is one of the reasons why: the Ngorongoro Crater where the wildlife is so abundant, so diverse, you almost can't believe your eyes. Just over the ridge of this magnificent place lies our destination and it's not easy to get there. After a day on planes, almost four hours of driving -- the last 40 minutes on rutted dirt roads -- under sprawling acacia trees, through coffee plantations and past villages, called camps, where the plantation workers live -- we entered the gates of the Rift Valley Children's Village -- and into another world.

Bill Whitaker: From the beginning, you called this the Rift Valley Children's Village?

India Howell: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: Not an orphanage? Why?

Rift Valley Children's Village

CBS NEWS

India Howell: Because my kids aren't orphans. They're not up for adoption. They never have been and never will be because they're home now.

India Howell runs this "home" - really a group of houses - with her business partner and managing director, Peter Leon Mmassy.

"...My kids aren't orphans. They're not up for adoption. They never have been and never will be because they're home now."

Bill Whitaker: You're the legal guardian for the children in the village?

Peter Leon Mmassy: Yes. I am the legal guardian. India and I, we are, I mean, two legal guardians, so she is Mom, and I'm Dad.

Bill Whitaker: They call you Mama?

India Howell: They call me Mama, and then after they've watched enough Disney movies, they start calling me Mom.

Bill Whitaker: Had you wanted to be a mom, have your own kids?

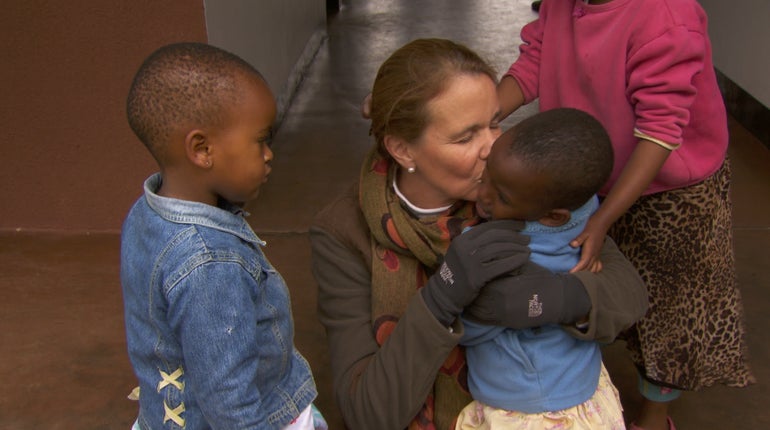

India Howell embraces one of her children

CBS NEWS

India Howell: Believe it or not, I don't think I was issued with the biological clock. As all of my friends became more frantic and started to marry people they would later divorce because they just wanted to have kids, I couldn't understand that drive. And here I am with more children than I can count. And I can't imagine any other way.

Bill Whitaker: These are all your kids?

India Howell: These are all my kids.

Bill Whitaker: So what do the kids get here?

Peter Leon Mmassy: I can ask you the same thing, I mean about your home. What do your kids get? So it's everything. When the kids come here it's-- this is home.

The Rift Valley Children's Village is located near the town of Karatu -- on nine acres of land donated by local villagers, with 90 employees, including social workers, counselors and support staff -- peppered throughout the year with many volunteers. There are 22 buildings, a third of which are the children's houses. Each house has two deputy moms -- called Mamas -- all Tanzanian. The children here range from toddler to 21. They get food, clothing shelter, education and love.

Like most large families, the kids have regular routines. They're up at dawn, get ready for school, and sit down for breakfast. There's snack time, play time, and like it or not, for Bobo and Esau - and everyone else -- bath time. Establishing traditions is a big deal here, right down to birthday celebrations. It might not be the exact date - but for a little boy like Eliasi, it's his day.

Eliasi's birthday celebration

CBS NEWS

Every child who ends up with India and Peter has a story - some more poignant than others.

Bill Whitaker: It seems that most of the children have lost their parents or were living with relatives. And just some of the descriptions we came across here: "Frightened and angry, mistreated emotionally and physically."

India Howell: Yeah. Oh, this sweet, little girl. She witnessed her father beat her mother to death, and was probably three or four years old. So old enough to see what was happening, but by no means old enough to have the -- to be able to emotionally process that. Then moved in with relatives where she was being sold, she was being prostituted out.

What India and Peter have undertaken is no easy feat... and it all started with a trip India took to Tanzania in 1998 - which had nothing to do with children.

Bill Whitaker: How did you end up here in Northern Tanzania?

India Howell: My mother asked the same question, many times; quite by accident, actually. I agreed to go climb Kilimanjaro with one of my best friends for her 40th birthday. I had no interest in Africa whatsoever, but stepped off the plane and knew that I was home.

Peter Leon Mmassy

CBS NEWS

The feeling was so strong that after the climb, India went back to the U.S., quit her job and applied for one with a safari company - she was hired and within three months was back in Tanzania.

Peter, who grew up in poverty, but managed to make it through high school, was working to earn money for college at a safari company. India became his boss.

Bill Whitaker: What did you think of her?

Peter Leon Mmassy: It was my first time to work under, I mean - a woman boss and an American woman boss. I was really impressed. And, she was smart and she had this sense of humor - and - but tough lady.

This tough lady grew up in an exclusive enclave on the North Shore of Long Island, New York, and was CEO of a business in Boston - a world away from Tanzania.

Bill Whitaker: So, you came here to work for a safari company?

India Howell: Right.

Bill Whitaker: And end up founding a children's village.

India Howell: Right, that seems like a big jump, but actually, there's a thread. So, part of my job required that I go to the city of Arusha every week and every time you got out of the car you were just swarmed with these ragged little boys, who, I soon discovered, were what we call "street children" here and my mission from the beginning was to identify these kids that are living at risk before they're driven to the streets.

Bill Whitaker: So how did you find out that you both had this interest, in helping needy children?

Peter Leon Mmassy: I wrote a proposal, very small proposal, about my home village. And I showed it to India. I said, "Ins, this is-- I'm really thinking that I want to do this."

The proposal suggested that through environmental conservation a community can not only sustain itself but more importantly enable children to thrive.

India Howell: He said, "You know, I've written a business plan." I said, "Oh, I'd love to see it."

Bill Whitaker: What did you think of this plan when you saw it? Was it--

India Howell: I thought it was brilliant.

Bill Whitaker: --this is realistic?

India Howell: I thought it w-- hm?

Bill Whitaker: Did you think it was realistic?

India Howell: I'm very practical in my-- no matter what idea comes to me, my first thought is, "And where does the money come from?" Because it doesn't matter if it's a good idea if you can't pay for it and sustain it.

So Peter's proposal was all but forgotten, then this happened...One of India's employees at the safari lodge told her he was not only quitting his job but abandoning his 3-year-old son, named Doctor. Just like that India was thrust into motherhood.

India Howell: There's this little peanut in a shuka, which is the fabric that the Maasai wear. And we just looked at each other. And it-- it was like we'd been looking for each other forever, and we finally found each other and he just ran into my arms and I was sunk for life.

Riziki, also abandoned by her birth parents, followed Doctor, then came Juma and India - named after her new mom. Now a full-time mother of four, India decided to leave the city of Arusha and the safari business and move to the countryside, where she rented a house on an old coffee plantation.

Word got out there was a lady taking in children. Over the course of 4 years, village and church leaders and relatives started dropping off abandoned and abused children -- some orphaned by AIDS. The family grew to 17 kids. Peter, in the meantime got his degree, became managing director and married his college sweetheart, Grace. They now have three daughters of their own.

Doctor, the first child she took in is now 19.

Doctor: There was something that Mom was showing that my family didn't have where it was love, care that came first before anything else.

Riziki is 21.

Riziki: At first I was so much afraid of her.

Bill Whitaker: Why?

Riziki: When we're little kids, I mean, they just tell us, like, the white people are bad people and when I saw her, at first I was, like, terrified.

Bill Whitaker: Actually terrified?

Riziki: Uh-huh (affirm). But as time went by I mean I got used to her and I wasn't afraid anymore.

Bill Whitaker: Now you love her?

Riziki: Very much, I do.

As it turns out giving kids a place to live is the easy part.

India Howell: I thought I had it all figured out. I-- you know, they can go to the local public school. And I realize this school isn't a school by my definition.

So India and Peter convinced the local elders to let them take over the administration of a primary school.

This is what the elementary school looked like before.

This is what it looks like today. Peter and India now run two schools - primary and secondary - for their kids and almost 700 local children -- like James and his friends who trek five miles every day to get here.The kids are taught in Swahili and English and they have the best scores and graduation rates in the region. Even so, to accomplish anything India has had to overcome Tanzanians' skepticism. Locals have seen Western good intentions come and go before.

Bill Whitaker: I know you've heard the criticism of the white woman, the white American, rushing in to save the Tanzanians. How do you-- how do you--

India Howell: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: --respond to that?

India Howell: I smile and nod. It-- it's-- it's very sweet and naïve that people think that it could be that easy. Her American assertiveness often clashes with the local culture. So Peter has the added title of diplomat: he smooths tensions between India and the community.

Bill Whitaker: You guys make a good team.

Peter Leon Mmassy: We are making a very good team -- and she drives me nuts. But I love that.

India Howell: If it weren't for Peter, I would've been deported, because he's always explaining me. He gets the American culture but he most importantly, gets what is needed here, and how to translate all of the different ideas into something workable.

The Rift Valley Children's Village runs on an annual budget of $1.3 million with the help of various family foundations and generous donors.

Still, India travels twice a year to the U.S. to raise money. Beyond the Children's Village, half of the budget pays for local schools, a microfinance program with 500 clients and a healthcare clinic that serves 8,000 people.

Bill Whitaker: Are you surprised by the success of the Children's Village? I mean, I know this was your dream long ago. But look at what you've brought about. Are you surprised?

Peter Leon Mmassy: I'm amazed. I'm astonished. I-- every single day, I live- I wake up, I'm, like, wow. Did we really do all of this?

© 2016 CBS Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment